Eyre De Lanux, Biography

Elizabeth Eyre de Lanux was born on March 20, 1894, the eldest daughter of Richard Derby Eyre (1869-1955) and Elizabeth Krieger Eyre (d. 1938).

See moreElizabeth Eyre de Lanux was born on March 20, 1894, the eldest daughter of Richard Derby Eyre (1869-1955) and Elizabeth Krieger Eyre (d. 1938).

As Elizabeth's mother suffered from depression, spending extended periods in a Summit, New Jersey sanitarium, the responsibilities of parenthood fell largely to Richard Eyre, a successful patent lawyer. The Eyres traced their origins to prominent Philadelphia shipbuilders. Richard Eyre was born in Florence, Italy. His father, Wilson Eyre (1823-1901), served as United States Consul in Venice during the period of Italian unification. Elizabeth's aunt was the sculptor Louisa Lear Eyre (1872-1953), and one of her uncles was Philadelphia architect Wilson Eyre (1858-1944). Elizabeth's sister, Louisa Lear Eyre Norton (1896-1966), entered M.I.T. in 1920, receiving the Ph.D. in Physics in 1924.

Elizabeth attended Miss Hazen's School in Pelham Manor, Westchester County, New York and enrolled in classes at the Art Students League in 1912 and during 1914-15. Her teachers were George Bridgman for Life Drawing and John C. Johansen for Still Life Painting. At this time, she resided at 47 Washington Square but soon moved to 15 W. 67th Street. She exhibited two paintings, "L'Arlesienne," and "Allegro," in the first annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917.

In early 1918, while working for the Foreign Press Bureau of the Committee on Public Information, Elizabeth met Pierre Combret de Lanux (1887-1955), a writer and former literary secretary to André Gide. At the time of their meeting, Pierre de Lanux was a member of the French High Commission to the United States, in charge of liaison with the allied nationalities of Central Europe. In this capacity, he spent the years 1916 to 1918 traveling between Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, New York, and Washington. Elizabeth and Pierre were married in New York in a civil ceremony on October 9, 1918. Immediately after the Armistice, they sailed for Paris, settling at Number 19 Rue Jacob. Their daughter, Anne-Françoise, nicknamed "Bikou," was born December 19, 1925.

Possibly from the beginning of their marriage, but certainly from the early 1920s, Eyre and Pierre accorded one another the freedom to take other lovers. From 1923 to 1933, Pierre de Lanux was based mainly in Geneva, where he worked for the League of Nations as director of the Paris Office. This arrangement allowed not only for periods of separation but also for a stream of affectionate correspondence and frequent reunions. The marriage endured until Pierre's death in March 1955.

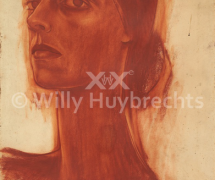

In Paris, from 1919-20, Elizabeth continued her painting studies with Maurice Denis at the Académie Ranson and with Paul Sérusier at the Académie Colarossi. She studied etching with Demetrius Galanis and took drawing classes at La Grande Chaumièe. At this time, she began signing her sketches "Eyre de Lanux." Café society at Le Boeuf sur le Toit was an inexhaustible source for portrait subjects, as were Natalie Clifford Barney's Friday salons. A series of "Outlines of Women," line drawings touched with wash, were exhibited in May 1921 at New York's Kingore Galleries. On view was Eyre's portrait of Barney, identified as "Amazone" in the exhibit leaflet, and those of various high-society figures, including Marion Tiffany, actress Eva Le Gallienne, and tennis champion Julie Lentilhon.

Eyre and Pierre resided in the United States from September 1920 to April 1922. New York society columnists noted the presence of "a most talented couple" at the Chelsea Hotel during the spring of 1921. While Pierre traveled to Chicago and Washington, most likely on diplomatic business, Eyre completed work on a pair of oak doors painted in tempera, vermillion, and gold with the 13th century legend of Sainte Marie l'Égyptienne. The doors went on exhibit in March 1922 at Knoedler Galleries and received a favorable review in The Sun. Eyre would not exhibit again in New York until 1943, when her fresco, "Persiennes, Persiennes" was included in "The Art of 31 Women Show" at Art of This Century Gallery.

Eyre began the study of frescoe painting in the late 1920s with Constantin Brancusi. Her first solo exhibit of frescoes opened on June 8, 1926 at the Galerie Aux Quatre Chemins. She would return to fresco painting intensively during her stay in Rome. Exhibits of her later frescoes were held in 1952 at Alexander Iolas in New York and in Paris at Le Sillon in 1960.

During her years in Paris, Eyre became acquainted with Pierre's friends: Valàry Larbaud, Léon-Paul Fargue, and Jean Cocteau. Ezra Pound made corrections to her 1923 poem "Rue Montorgueil." In 1926, she produced etchings for Larbaud's Le Pauvre Chemisier (1929). Eyre knew Adrienne Monnier well enough to regret not having won her complete acceptance; her painting of Monnier's sister, Rinette, had been exhibited in the 1921 Kingore show. It may have been at Monnier's bookshop, La Maison des Amis des Livres, in 1919 or 1920, that Eyre met Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, who immediately fell in love with her. Aragon's 1919 poem, "Isabelle," dedicated cryptically to one "Madame I.R." on its 1926 publication, tells of his love for "une herbe blanche." Aragon makes Eyre the muse of the Buttes-Chaumont in his Le Paysan de Paris (1926), and in "Le Songe du Paysan" he describes the origins of his secret love. Their one-year liaison began in earnest in March 1925, soon after Eyre's relationship with Natalie Barney had ended. An affair with political writer Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, initiated in early 1923 and carried on intermittently, also ended at this time.

In 1933, with the advice of one "A.D.," perhaps painter André Derain, Eyre and Pierre purchased a number of works of contemporary art. These included a Picasso watercolor and drawing from his Cubist period, a Braque, a Berman, two Picabia drawings, an Yves Tanguy, a large Mirà, and two paintings by de Chirico. In future years, the painter and gallery-owner Betty Parsons (1900-82), whom Eyre doubtless knew in Paris, would assist her in selling paintings from her collection. Many would be sold at a great loss to meet expenses.

From 1927 to 1933, Eyre collaborated with British carpet designer Evelyn Wyld (1882-1973), creating modernist furniture in glass, cowhide, wood, and lacquer for private clients. Eyre met Wyld while interviewing her for her monthly column, "Letters of Elizabeth," which ran for two years in Town and Country magazine. In 1927, she accepted Wyld's invitation to join her "Atelier du Tissage" on the Rue Visconti, but continued to maintain her own apartment. Eyre and Wyld exhibited their interiors in the 1928 and 1929 annual showings of the Artistes-Décorateurs and in 1930 at the first exhibit of the Société Union des Artistes Modernes. In 1932, the two women opened Décor, a furniture gallery in Cannes. The business, hurt by a decline in demand following the 1929 stock market crash, closed in 1933.

While she was involved with Wyld, and perhaps inspired by their partnership, Eyre began investigating related means of making a living. She spent from November 1927 to April 1928 in the United States. In Lake Forest, Illinois, in association with the architect David Adler, she designed a dining room for Isabelle and William Clow, Jr. Other projects occupied her, and while none were ever realized, she wrote about her ideas in lengthy letters to Pierre: becoming an intermediary between French decorators, such as Jean Michel Franck, and American retailers, such as Saks Fifth Avenue; opening an interior design gallery in Paris; and, related to her interest in native American design, organizing an exhibit of American Indian art that would travel throughout Europe.

In 1938 and 1939, During the Spanish Civil War, Eyre traveled to Spain, arousing her father's concern. After the outbreak of war in Europe, Eyre returned to New York from Barcelona. Pierre joined her in February 1940 and the family remained there during the war. After a career as a lecturer on international relations from 1928 to 1934, Pierre had begun teaching in 1935 at Middlebury College during summer sessions, serving eventually as head of the Department of Contemporary Civilization. Bikou was then a student at the Putney School in Vermont.

The years immediately following the end of the war were ones of great change for Eyre. She returned to Paris in 1945 and was often at the Café de Flore in the company of Picasso and Brancusi, Chilean writer Pablo Neruda, the French premier Albert Sarraut, and photographer Robert Capa. In March of 1948, she journeyed to Rome. At the Hotel d'Inghilterra, she met a young Italian writer, Paolo Casagrande. Eyre was 54 years old and he roughly half her age. With his encouragement, she rented a studio at 53 Via Margutta and began working on large frescoes and fresco portraits. One of her sitters was Tennessee Williams.

The relationship with Casagrande endured until the end of Eyre's life. Although Casagrande married in 1950 and eventually had children, he and Eyre attempted to see one another whenever possible and maintained an almost continuous, passionate correspondence. They traveled for long periods in southern Italy, Sicily, Greece, and Morocco. During their Moroccan sojourn in 1951 and 1952, Eyre began making notes for short stories. "La Place de La Destruction" was published in 1955 in La Nouvelle Revue Française, and "The House in the Medina" appeared in Harper's Bazaar in November 1963. Her sketchbooks, watercolors, and frescoes from this period reveal her fascination with the North African landscape.

Throughout the 1950s, Eyre visited her widely-scattered loved-ones: Evelyn Wyld at her home "La Bastide" near Nice, Lisette de La Selle in St. Tropez, Consuelo Ford in New York, and Alice de Lamar in Palm Beach. She stayed for long periods with her sister in Greenwich, Connecticut and with friends in New York.

In March, 1961, possibly in order to pull away from Casagrande, Eyre left Paris and returned to New York permanently, taking a studio apartment at The Picasso on East 58th Street. In a diary entry made shortly before moving day, she wrote, "Write to Paolo every day, and mail it only occasionally." She was reunited now with friends of forty years: Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Monroe Wheeler, Eugène Jolas, and Betty Parsons. And yet she could not long remain away from Rome. She returned in 1964, 1967, 1968, 1969, and 1978. In March of 1969, fulfilling a long interest in Japan and Zen Buddhism, she embarked for Tokyo, Kyoto, Bali, and Bangkok. She also made several visits to Bucharest, Romania for the purpose of receiving a youth-enhancing hormone injection from Dr. Ana Aslan, a Romanian physician. Her last visit to Paris occurred in 1978. Until legal blindness overtook her, Eyre pursued various research and writing projects. She began work on a biography of Tobias Lear, a secretary to George Washington and a distant maternal ancestor. She also gathered photographs for "Illusions of Identity," a book of associations between the physical and metaphysical worlds with a preface by Ray Bradbury; the book was never published. In 1980, she supplied paintings to illustrate Overheard in a Bubble Chamber (1981), a book of science poems for children written by her close friend Lillian Morrison. The New Yorker magazine published three of her short stories: "Montegufoni" (1966), "Cot Number Eleven" (1968), and "Putu" (1972). Plans to bring together twelve stories in one volume were never realized.

Eyre de Lanux died in August 1996 at the age of 102.